Initial Commit: FRC team 2415's code ported to the AdvantageKit framework

Snapwhiz914 / October 2024 (1081 Words, 7 Minutes)

Background

Next year marks the last season I can participate on my school’s FRC team. When I joined, software was not our team’s priority, to say the least. Thankfully, as the seasons went by, the software sub-team learned from past mistakes to iterate robot code to improve reliability and functionality. Now that I’m the software lead, it’s my turn to continue our progression, and I think the best direction to go is towards the code of Team 6328 Mechanical Advantage. This post explains what Mechanical Advantage’s framework is and my process of completely refactoring our 2024 season code to match it.

Quick Intro to FRC robot code

FRC is a high school robotics league run by FIRST. Most teams program their robots in Java within the WPILib ecosystem, a toolsuite and API for running code on the robot’s computer.

WPILib heavily encourages teams to use their command-based framework, which organized mechanisms on the robot into Subsystems and actions on the subsystems into Commands. In my experience it is an easy way of thinking about robot control, especially for robots with many mechanisms and movements. Subsystems expose commands to move themselves, and driver inputs can trigger chains of these commands to perform complex actions quickly, without relying on timing or threading.

Why use Mechanical Advantage’s framework

What got me interested in the Mechanical Advantage framework (which is built on top of the command-based framework) is the separation between subsystem control logic and motor control, the latter of which is called the “IO” layer. This has three significant advantages:

- From a project structure standpoint, it is cleaner. Instead of one class that contains subsystem logic and IO objects, the ownership is split into multiple classes with less lines.

- There is no limit on the number of IO classes you can have. This means that you can switch out motor types (ie. a TalonFX or a Neo 550) on the physical robot and only change one line, provided that there is an IO class for it.

- Last, but definitely the most important advantage, is simulation ability. Instead of handling simulation logic within the subsystem class, all of it can be moved into its own IO class.

The second main benefit of the Mechanical Advantage framework is their logging system AdvantageKit. I’m not going to go into details here because of how elegantly they put it on their website, so I’ll give a quick summary: a logging system that lies within the subsystem and records all inputs to it, so that inputs can be replayed from a log to diagnose problems quickly and simulate robot code without a physical robot available.

Simulation is extremely important early in the build season. While the physical robot is not available, a simulated model allows teams to test their code’s logic before deployment. Mechanical Advantage provides a log viewer called AdvantageScope. Again, I’ll summarize: an incredibly feature-rich log viewer/visualizer that makes problems very easy to spot.

The porting process

Before: WiredCats2024

In all honesty I was very happy with our code this year. We finally used the Command Based framework, which organizes motor outputs into their own self-contained commands that are linked to inputs from the driver. I was pleased with its readability, reliability and the code structure that came with it. Compared to the 2023 season it was very easy to add a new button bind for the driver or a new command for an autonomous routine.

During the season and especially after reading code from other FRC teams on Github, I found some room for improvement:

- Following is the constructor for one of our subsystems:

motor = new CANSparkMax(RobotMap.Finger.FINGER_MOTOR, CANSparkMax.MotorType.kBrushless); // initialize motor configureMotor(); configureMechansim2dWidget(); relativeEncoder.setPosition(0); offset = 0; pidController.setReference(0, ControlType.kPosition);There is such a thing as too much abstraction, and such a thing as too little abstraction. The above code falls on the too little side. From the constructor alone, this class clearly has more than one responsibility: controlling its motor, a visualization widget and offsetting the motor’s set position. Ideally, this subsystem class would only be concerned with setting the motor’s position. Visualization could be handled in this class, but motor control takes lots of screen space and is very distracting when trying to code in a hurry. Instead motor control should be handled in its own class.

- Here’s a method from our Arm subsystem:

private double getPotRotations() { double measure = Constants.Arm.MAX_ANGLE - (((input.getAverageVoltage() - Constants.Arm MIN_VOLT) / (Constants.Arm.MAX_VOLT - Constants.Arm.MIN_VOLT)) * Constants.Arm.MAX_ANGLE); return measure; }First of all, the code formatting is very strange here. Why is the char count limited to 150, instead of the standard 120? Why is the final multiplication tabbed six times? I’ve been working on establishing an automatic, lambda-friendly linter for the new project to avoid this.

This function converts a voltage from a potentiometer within a known range of minimum and maximum voltages and returns the corresponding angle measure. This is one of two sensors that does not have its own dedicated class, the other being the infrared break beam sensor. Ideally this function is inside of its own class, labeled appropriately, and takes class variables for its constants instead of going to the constants file directly.

After: WiredCats2024Akit

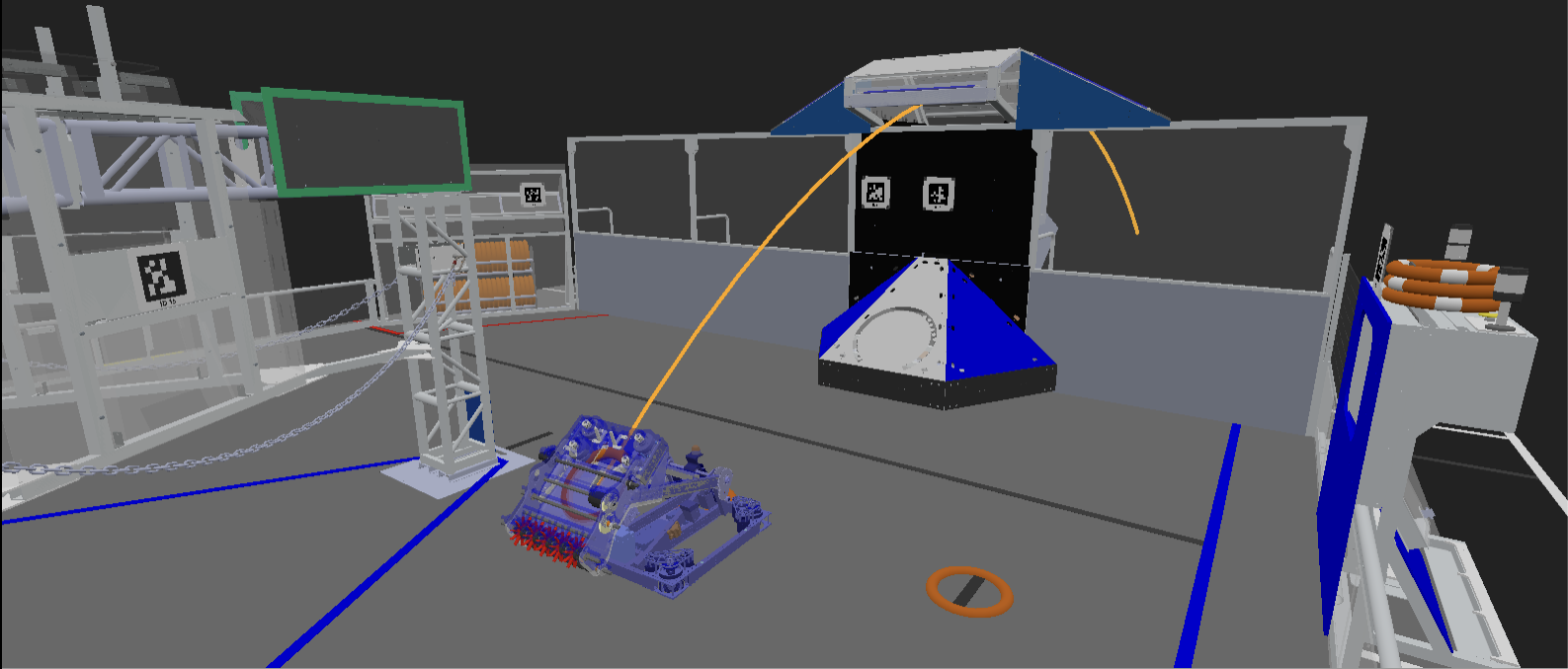

A simulation of the robot, produced with AdvantageScope

A simulation of the robot, produced with AdvantageScope

WiredCats2024Akit in its current state is exactly what I was looking for when I originally had the idea. I started with the subsystems, adding an IO layer to all of them. Then I reorganized the constants and applied other small changes, moving code around along the way. Then I focused on the highlight of WiredCats2024Akit: simulation and visualization. I created sim IO layers for every subsystem, a simulated environment class that kept track of the robot’s interactions with the game objects and visualization classes that managed the position of the robot’s components and game objects so AdvantageScope would display them correctly.

I had one final goal after that: game piece shooting and trajectory visualization. During the season I took some testing videos of autonomous routines, and I was able to approximate the exit velocity of the game piece as it left the flywheels. I created a class that moved a 3d pose through the air following the projectile motion parametric equation, and actually simulated a game piece flying through the air. From there it was easy to create an array of 3d poses for AdvantageScope to visualize a trajectory line, which is pictured above.

Future plans

While I have achieved my original goals with this project (better architecture and simulation), I realized that it has also become a platform for me to experiment with new ideas. I have a running list of features that I want to add on the project’s README.md

I’ll make posts of features that are big enough to deserve one.